Beyond coastal erosion: A comprehensive assessment of climate change impact on SIDS ecosystem, society and economies.

Rising Tides, Sinking Futures: Climate Challenges in SIDS. Delve into the multifaceted effects of climate change on small island nations.

Climate Change and its effects on Small Island Developing States (SIDS)

The Small Island Developing States (SIDS), although small in size, are home to over 65 million people, spread across more than 1000 islands. These small nations are amongst the most vulnerable to climate change effects, which will gradually increase if appropriate actions are not implemented as soon as possible. Due to close connections between human communities and coastal environments, SIDS are particularly exposed to hazards associated with the ocean and cryosphere, including sea-level rise, extreme sea levels, tropical cyclones, marine heatwaves, and ocean acidification.

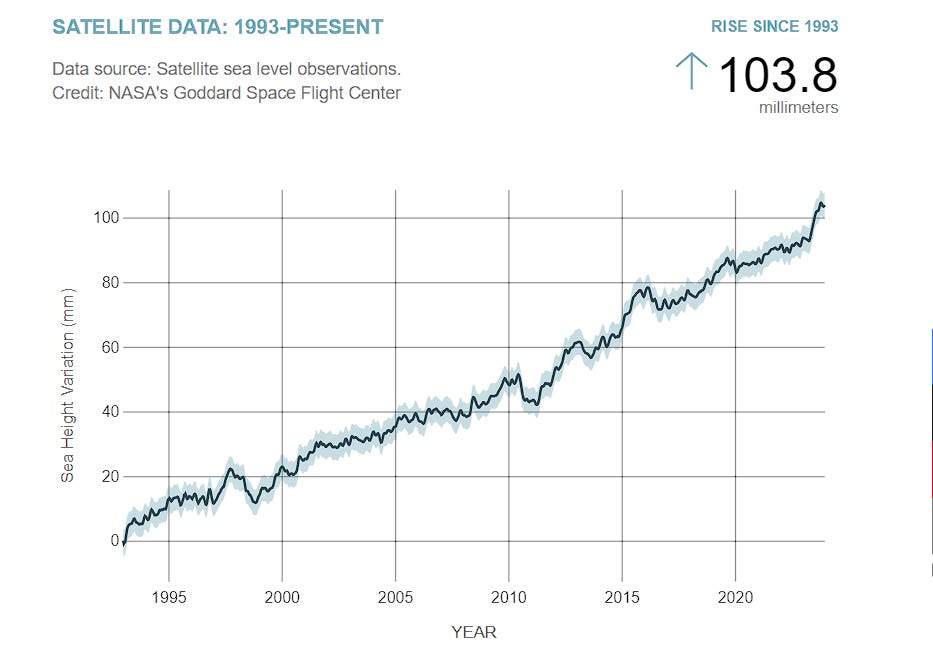

Global mean sea level is currently rising at an unprecedented rate of 3.6 mm per year as compared to the past century, and extreme wave heights have also increased. Under high emission scenarios, there may be multi-meter sea-level rise in the next decades to come. The anthropogenic climate change has also already resulted in increased levels of precipitation, higher storm surges, faster winds, and increased intensity of tropical cyclones. Hazards beyond the ocean and cryosphere also have implications for SIDS (Table 1). Atmospheric temperature extremes have already increased in frequency and intensity in SIDS and are projected to continue along this trend.

The Caribbean SIDS may experience up to six months per year of warm spell conditions, with a global average temperature increase of 1.5°C. Heavy precipitation events in SIDS have also increased in frequency and intensity and are expected to further increase. While patterns vary among islands, many SIDS will face increasing drought and reduced levels of annual precipitation as global temperatures rise, leading to freshwater stress.

Sectors that are critical to many SIDS’ national economies such as tourism, fisheries, and agriculture are reliant on environmental conditions and are thus affected by any changes to the environment. For example, coastal-based tourism makes up more than 20% of the national gross domestic product (GDP) for more than half of SIDS and more than 50% of the GDP for particularly tourism-dependent islands. This makes these sectors, and resultantly the economic stability of these countries, sensitive to any environmental change brought about by climate.

SIDS are also economically vulnerable to extreme events and resultant disasters. A common feature of SIDS is a high ratio of coastline-to-land area, with large portions of populations, infrastructure, and assets being located along the coast. Moreover, SIDS have significant portions of their populations and assets in locations that are exposed to climate hazards. Many of these island nations are also located in the tropics and subtropics. These physical locations result in high exposure to changes in sea levels, coastal erosion, extreme sea-level events, tropical storms, and flooding.

Climate change is recognized as one of the most important factors affecting agriculture water supply and food security in SIDS. Risks include instability of food supply, disruption to food access, and changes to crop yield and food availability. On many small islands, including SIDS, freshwater stress is expected to occur as a result of projected aridity change.

SIDS are particularly at risk due to the large proportion of the population whose livelihoods are dependent on agricultural production. Several SIDS rely on high-value crop production such as bananas and plantains as significant contributors to labor and livelihoods. These crops are adversely affected by hurricanes, floods, and droughts, and those impacts are expected to become more extreme with climate change.

Further threats include fungal diseases, which threaten the sustainability of banana industries in SIDS. Due to the sector's heavy reliance on freshwater, agriculture is particularly vulnerable to potential reductions in freshwater availability in the future.

Exposure to change in sea level

Rise in sea level poses a serious threat to coastal life around the world. There are mainly two factors that results in the rise in sea level, Global Warming: The added water from melting ice sheets and glaciers, and The expansion of seawater as it warms. Small Island Developing States (SIDS), a distinct group of developing countries, experience significant vulnerability to climate change in general and Sea Level Rise (SLR) in particular due to the large portions of people, assets, and infrastructure located in the coastal zone.

SLR has been a climate change hazard of particular concern for island nations since adoption of the Barbados Programme of Action in 1994 that detailed the particular challenges of achieving sustainable development in SIDS. Current SLR impacts in SIDS include land-loss and coastal erosion, increased coastal flooding from tides, storms and waves, and increased.

salinization of coastal aquifers, and has resulted in contraction of habitats, shifts in the geographical location of coastal species, loss of biodiversity and reduction in ecosystem services.

Human and infrastructural impacts include loss of homes, human displacement, loss of lives and livelihoods, economic sector disruption, increased water insecurity, and disruption to key infrastructure such as transportation and communication.

Natural disasters

Small Island developing states (SIDS) are amongst the most vulnerable to natural disasters and disturbing weather events. With an increasing frequency over time, they are regularly hit by severe storms and other disasters, causing on average an annual damage of 2.1 percent of GDP.

Tropical cyclones (TCs) are amongst the costliest and deadliest natural hazards and can cause widespread havoc in tropical coastal areas. Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are particularly vulnerable to TCs, as they generally have limited financial resources to overcome past impacts and mitigate future risk. Violent winds, floods, and droughts have had severe consequences for millions of people and currently present an increasingly significant challenge for development and poverty alleviation in small island states.

However, although islands tend to have similar geographical features, natural hazards produce widely different outcomes in different island states, indicating great variation in vulnerability. While some islands seem to cope and adapt fairly well, others suffer tremendously. That is, the impact of natural hazards of the same physical magnitude ranges from going more or less unnoticed or causing only small disturbances to resulting in severe catastrophe.

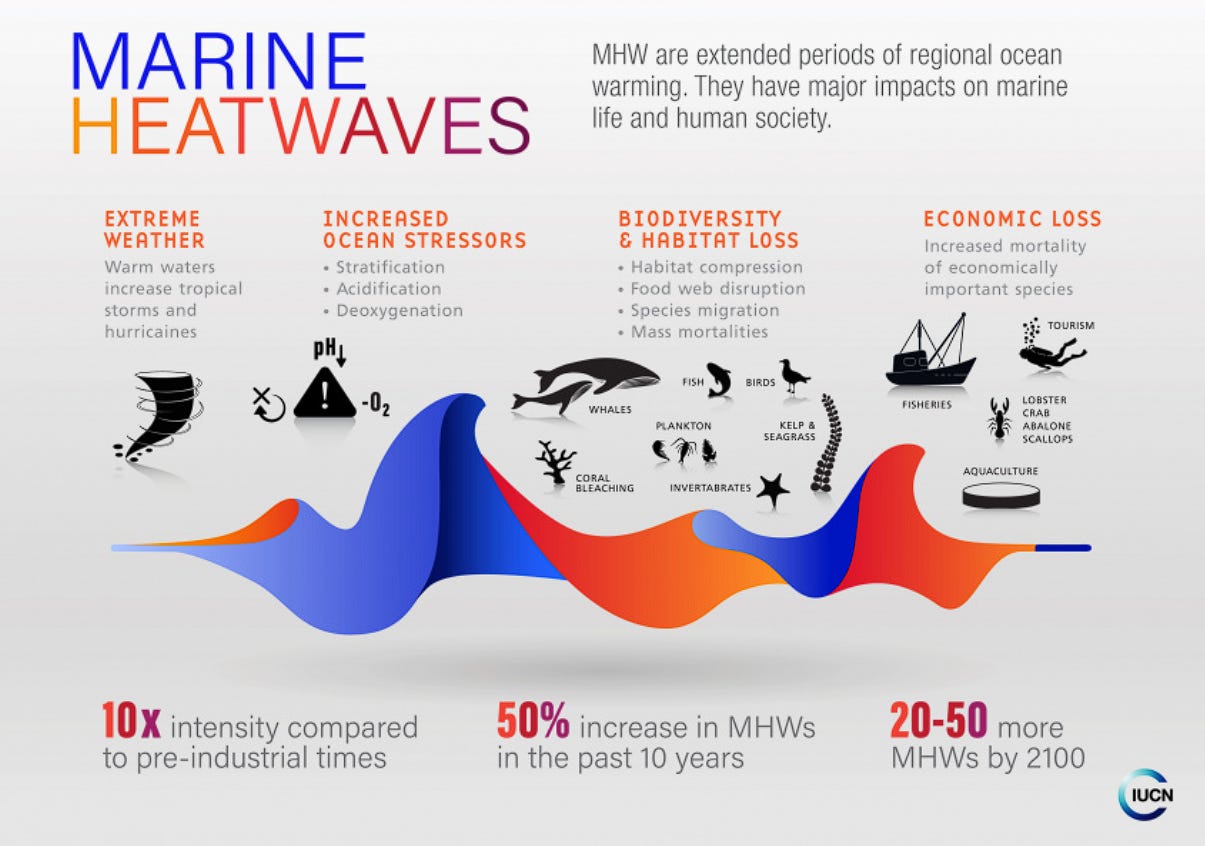

Marine heatwave(s)

A Marine Heatwave (MHW) is a period of abnormally high ocean temperatures relative to the average seasonal temperature in a particular marine region. MHWs have increased by 50% over the past decade and now last longer and are more severe.

MHWs can last for weeks or even years. They can affect small areas of coastline or span multiple oceans. MHWs have been recorded in surface and deep waters, across all latitudes, and in all types of marine ecosystems. Increasing average water temperatures reduce marine ecosystem’s tolerance to local temperature rises.

As MHWs become more frequent and extreme they risk pushing ecosystems beyond their threshold of recovery; with lasting consequences for marine biodiversity, and many millions of people whose livelihoods depend upon it. Among the species most sensitive to MHWs are those that form the basis of the most biodiverse marine ecosystems: kelp forests, seagrass meadows, and coral reefs. The severe event affecting the west coast of Australia in 2011, for instance, wiped out entire ecosystems causing some species to disappear for hundreds of kilometers.

MHWs are not the only threat to marine ecosystems; often they occur alongside other stressors such as ocean acidification, deoxygenation, and overfishing. In such cases, MHWs not only further damage habitats, but also increase the risk of deoxygenation and acidification.

MHW’s extensively threatens the biodiversity, livelihood and economic means of SIDS.

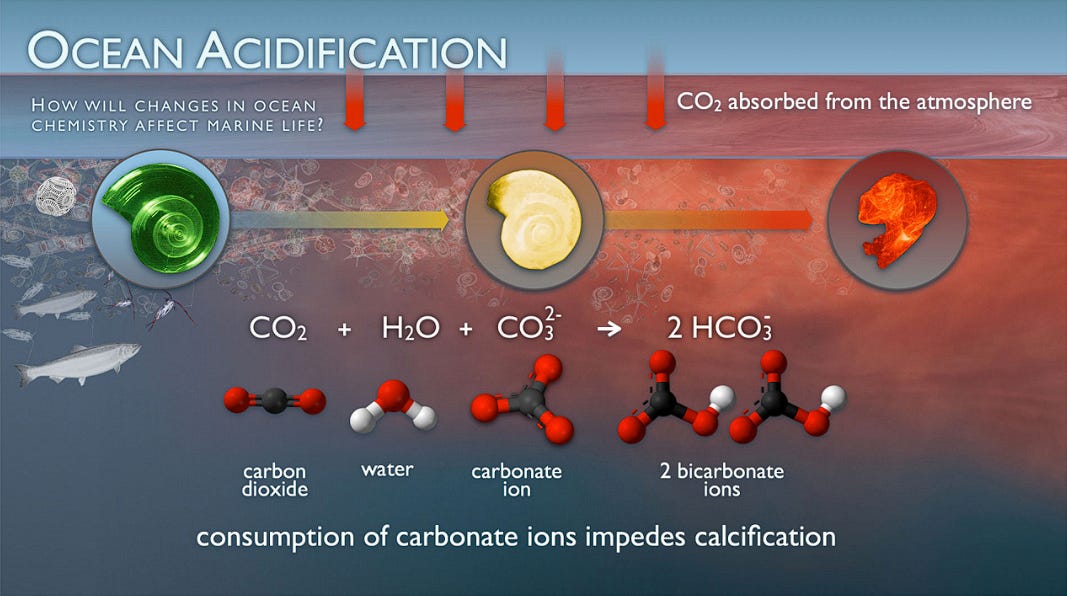

Ocean acidification

Ocean acidification refers to the decrease in the pH of the earth’s ocean, caused primarily by the uptake of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. The ocean absorbs about 30 percent of the CO2 that is released in the atmosphere, and as levels of atmospheric CO2 increase, so do the levels in the ocean. Decreased ocean pH has a range of potentially harmful effects for marine organisms. These include reduced calcification, depressed metabolic rates, lowered immune responses, and reduced energy for basic functions such as reproduction. The effects of ocean acidification are therefore impacting marine ecosystems that provide food, livelihoods, and other ecosystem services for a large portion of humanity.

Some 1 billion people are wholly or partially dependent on the fishing, tourism, and coastal management services provided by coral reefs. Ongoing acidification of the oceans may therefore threaten food chains linked with the oceans.

SIDS are highly dependent on natural resources such as coral reefs for livelihood. Coral reefs are important for subsistence, fisheries, tourism and shoreline protection. Seven of the world’s top ten most dependent countries on coral reefs for economic means are SIDS

Ocean Acidification will lead to the decrease in the ability of marine calcifies to produce calcium carbonate, while the rate of bioerosion and dissolution could increase. Other calcifying organisms such as components of the phytoplankton and the zooplankton, which are a major food source for fish and other animals may also be affected. Many SIDS have surficial geology made of coralline limestone, acidification of the ocean may lead to dissolution of the material and increased erosion.

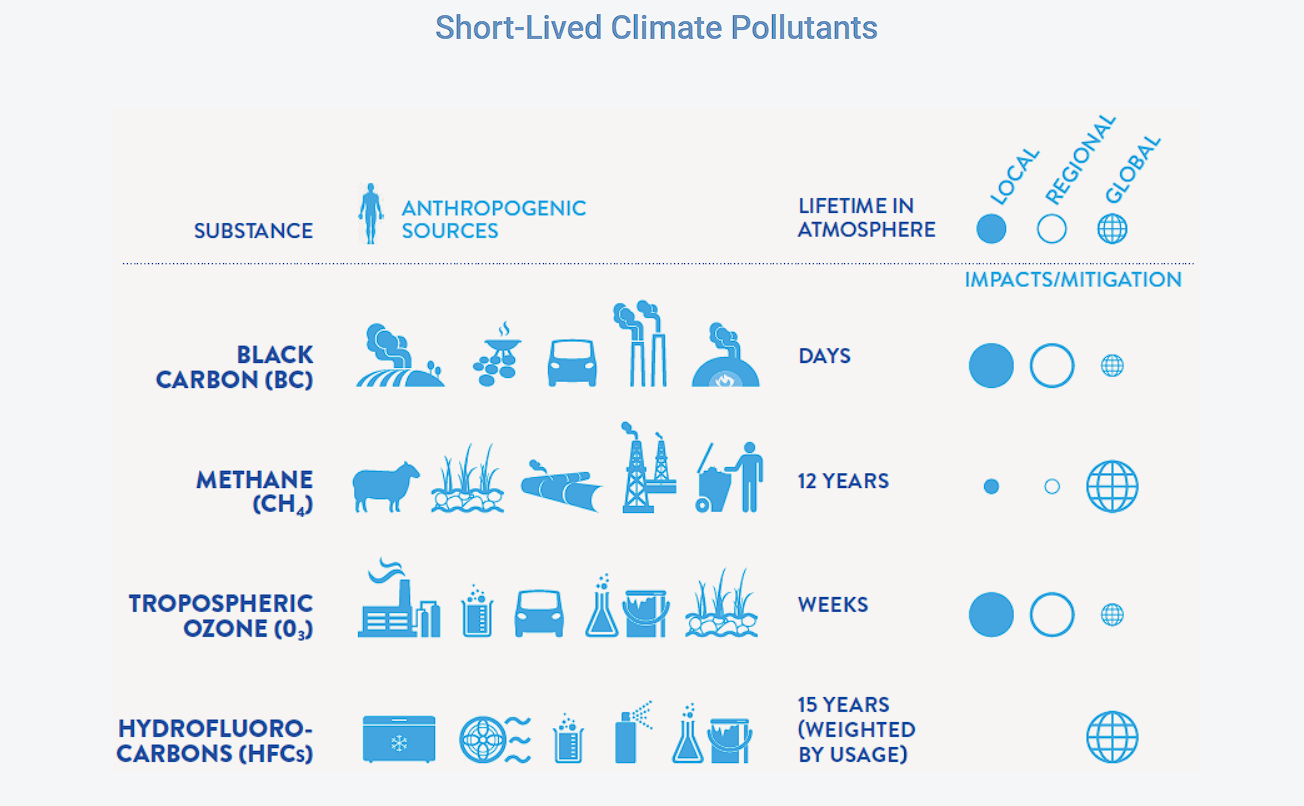

Short Lived Climatic Pollutants (SLCP)

Short Lived Climatic Pollutants (SLCPs) are a group of greenhouse gases and air pollutants that remain in the atmosphere for a much shorter period of time than carbon dioxide, yet their potential to warm the atmosphere can be many times greater. Certain short-lived climate pollutants are also air pollutants that have harmful effects for people, ecosystems and agricultural productivity.

The Short-Lived Climatic Pollutants such as Black Carbon, Methane, Tropospheric ozone and Hydrofluorocarbons (HFC), are the most important contributors to anthropogenic global warming. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that only way to slow warming in the near term and achieve the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 1.5°C, is to take action on short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs).

Cutting short-lived climate pollutants in areas such as waste management, transport, and cooling also promises localized advantages for SIDS by reducing black carbon, methane, and hydrofluorocarbons, which damage local agricultural production and public health. In SIDS the consumption of these SLCPs is driven by essential industries such as tourism and fishing, so finding sustainable alternatives is essential. Black carbon is also produced in the agricultural sector by open burning of agricultural residue, which reduces crop yields and disrupts rainfall patterns.

Some of the General problems faced by SIDS are:

Isolation and negligence from rest of the world-

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) face a unique set of challenges due to their geographical isolation, limited resources, and vulnerability to external shocks, including climate change. Despite their significant contributions to global biodiversity, culture, and heritage, SIDS often face isolation and negligence from the rest of the world, which exacerbates their vulnerabilities and hinders their sustainable development efforts.

Geographical Isolation:

SIDS are located far from major markets and economic centers, making trade, transportation, and communication more challenging and costly. This isolation limits their access to markets for their goods and services, hampers economic development, and increases dependence on imports.

Limited Resources and Capacity:

SIDS often have limited natural resources, human capital, and financial resources, which constrains their capacity to address development challenges, implement climate change adaptation and mitigation measures, and achieve sustainable development goals.

Vulnerability to External Shocks:

SIDS are highly vulnerable to external shocks, including economic downturns, natural disasters, and climate change impacts, due to their small size, limited economic diversification, and dependence on a few key sectors such as tourism, agriculture, and fisheries.

Neglect and Marginalization:

Despite their unique vulnerabilities and challenges, SIDS often feel neglected and marginalized in global decision-making processes, international development agendas, and climate negotiations. Their voices and concerns are frequently overlooked or sidelined by major powers and international institutions, limiting their influence and representation on issues that directly affect their future and well-being.

Inadequate International Support and Assistance:

SIDS often receive inadequate international support and assistance to address their specific development and climate change challenges. Despite commitments from the international community to support SIDS through financial assistance, technology transfer, capacity-building, and other forms of support, implementation gaps, delays, and insufficient funding often limit the effectiveness of international assistance and hinder SIDS' efforts to build resilience and achieve sustainable development.

Endangered resources in SIDS which affect livelihood-

SIDS are small islands and low-lying coastal countries that share similar sustainable development challenges. Many SIDS are already faced with crises in managing their limited and degraded natural resources. Strategies for conserving, protecting, and enhancing these resources should be based on the specific resource constraints faced in any given location, as well as the current and desired improvements in reversing depletion and degradation.

There is a high degree of dependency on limited natural resources because of the small size and economies of many SIDS; this is mainly within the agricultural sectors of crop production, livestock, fisheries, aquaculture and forestry. Higher and increasingly competing demands for food are accelerating the degradation of natural resources and ecosystems.

This affects the food supply and income of smallholders. The situation often increases their vulnerability and creates a vicious cycle of poverty, further degradation and hunger. The future of many island communities is threatened without sound management of natural resources and the environment.

In SIDS exploitation by foreign fleets under licensing agreements (or outside of them) is often unchecked and inshore and reef fisheries are often poorly managed. Coastal inshore areas are some of the most environmentally diverse and many ecosystems, especially coral reefs, are under threat from human activities as well as the impacts of climate change. Fishery resources are overexploited in many places, especially coastal waters.

The sustainable use of natural resources and the environment to produce goods and services in agriculture, livestock, forestry and fisheries depends largely on the way in which individuals, communities and other groups are able to gain access to land, fisheries and forests. Responsible governance of tenure of land, fisheries and forests is essential to ensure social stability, sustainable use of the environment, responsible investment for sustainable development and the eradication of poverty and food insecurity in rural areas.

Agriculture based livelihoods are already negatively affected by the impacts of a changing climate. Some suggestive solutions given by the international forum to solve livelihood degradation in SIDS are:

The IPCC 5th Assessment Report (IPCC AR5, 2014) summarized that adaptation to climate change generates larger benefit to small islands when delivered in conjunction with other development activities such as disaster risk reduction and community-based approaches.

Appropriate international assistance to undertake adaptation and mitigation programmes should be strengthened, but caution is needed to ensure such assistance is not driving the climate change. agenda in small islands. The risks and vulnerabilities of SIDS come from well beyond their borders and this is why the challenges facing SIDS need to be seen from a global perspective.

SIDS have been described as “data poor”, and policies adopted and implemented have been derived on the basis of little or no data and less information (ECLAC, 2003). Sound predictions on the effects of climate change on the regions’ natural resource base require support from models using local data. Often such information is very limited reflecting the scarcity of local climate records of sufficient length and accuracy. However, these data are essential for promoting policies, technologies and practices that build producers’ resilience to climate change and contribute to sustainability.

Resilience can be enhanced through co-constructed policies, strategies and plans and measures, such as flexible fishing strategies and the introduction of pest-resistant varieties and breeds.

It is also essential to diversify agricultural livelihoods to enhance domestic production and consumption in support of food security. In some cases, it may not be possible to modify existing livelihoods and so new livelihood options may be necessary. A priority activity, common to all SIDS to reduce vulnerability and increase resilience in rural areas is through diversification of agriculture. Diversification through integrated farming systems remains a key action for smallholders. This requires the identification and adoption of appropriate adaptation approaches for their needs.

In the Pacific SIDS, coconuts can tolerate salinity and are highly adapted to the coastal zones. Priority should be given to planting them in these areas to mitigate coastal erosion and sudden sea water intrusion due to tsunamis and typhoons.

In the Caribbean SIDS, characterized by a high exposure to natural disasters, it is necessary to enhance their climate change adaptation and promote policy reform. Some proposed measures include emergency assistance for small farmers, more sustainable and adaptive use of agricultural biodiversity, sustainable management of land, water and other natural resources through the development of diversified farming systems such as agroforestry and freshwater aquaculture, and the use of natural resources for bioenergy.

Threatened biodiversity of SIDS:

Island biodiversity refers to the unique variation of living organisms in an ecosystem- from mammals to bacteria. Islands often have precious and rare biodiversity systems because they tend to be small, insulated locations and species are often highly specialized to suit their environments, adapting to niche conditions. SIDS are home to a rich diversity of unique and endemic species, including plants, animals, and marine life, which are adapted to their specific environmental conditions and habitats. These ecosystems provide a range of ecosystem services, including food and water provision, climate regulation, and cultural and recreational values, which are essential for the well-being and livelihoods of local communities.

Some major biodiversity hotspots and their specialities are:

The Caribbean houses 10% of the world’s coral reefs and approximately 1,500 species of fish and marine mammals. The reef surrounding the Caribbean provides wintering and nursing grounds for many Northern Atlantic migratory species, including the humpback whale and the endangered American crocodile.

Islands in the Pacific region play host to 476 globally threatened species. Over half of the world’s known species of cetaceans, the majority of remaining dugong populations, and the largest groupings of hawksbill, green, and loggerhead turtles are also found in the marine regions of Pacific SIDS.

Ecosystems in the East Melanesian Islands’ Coral Triangle support 75% of known coral species (nearly 600), six of seven species of marine turtle, approximately 2,000 species of reef fish, and large populations of commercially valuable tuna.

The World Wildlife Fund’s Global 200 list, which prioritizes ecosystems for conservation, includes five outstanding coral ecoregions in the Central Indo-Pacific SIDS: the Bismarck-Solomon Seas, the New Caledonia Barrier Reef, the Palau Maine, the Tahitian Marine, and the Fiji Barrier Reef.

The Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA) is one of the largest UNESCO World Heritage Sites and is the largest marine protected area in the Pacific. It is the first island in the Pacific to contain deep-sea habitats with eight atolls and two submerged reef systems, with the average depth of the water more than 4,500 meters.

The islands in the AIMS region are extremely ecologically diverse and feature numerous ecosystems and biomes. Coastal and marine habitats include beaches, dunes, coral reefs, and mangroves. AIMS are host to “reef islands,” where coastal vegetation, like mangroves, protect shores which could otherwise be vulnerable to erosion.

The Indian Ocean is home to 10,000 shallow water marine species, including 2,000 fish and four species of marine turtles. The hawksbill, green, and loggerhead turtles are all on IUCN’s Red List ranging from critically endangered (hawksbill) to endangered (green and loggerhead). Nesting sites of particular importance for sea turtles exist in Comoros and Seychelles as well.

Terrestrial biodiversity

Many SIDS, particularly those in the Caribbean and the Pacific, are characterized by lush tropical rainforests, which are home to a diverse array of flora and fauna. These ecosystems are vital for carbon sequestration, climate regulation, and soil conservation, as well as providing habitat for numerous endemic and endangered species. Dry forests and scrublands are prevalent in SIDS with arid and semi-arid climates, such as those in the Caribbean, Indian Ocean, and South Pacific. These ecosystems are adapted to low rainfall and high temperatures, and they support a unique assemblage of drought-resistant plants and wildlife, including endemic species and rare habitats.

The Pacific Sheath-tailed Bat is classified as Endangered by the IUCN Red List. All four subspecies of the Bat have slowly disappeared from some of the Pacific Island nations where they were historically found.

Approximately 350 species of birds which breed in North America annually migrate to the Caribbean for the winter. During the summer months, a smaller number of birds migrate to the Caribbean from South America to mate and lay eggs. As a result, birds in the Caribbean, endemic or otherwise, represent the linkages between the neighbouring regions and their ecosystems.

There are 384 bird species in Singapore. More than 50% of birds in the Indian Ocean islands are endemic to Singapore.17 There are 15 endemic species of bird on the islands of the Comoros.

The Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity considers the species in SIDS to be at the greatest risk of extinction. In fact, of all the species extinctions worldwide, the majority have occurred on islands:

95% of bird extinctions, 90% of reptile extinctions, 69% of mammal extinctions, and 68% of flora extinctions.

Common threats include:

Climate Change

• Overexploitation

• Poaching

• Unsustainable hunting

• Illegal wildlife trade

• Clearing of forests and grasslands

• Draining wetlands for agriculture and cities

• Fragmentation of harmful species into foreign ecosystems

• Pollution

• Diseases

• Natural Disasters

Climate change is the greatest threat to biodiversity across the globe. Marine biodiversity, of great importance to many SIDS, is threatened by continued pollution, sedimentation, marine diseases, and overfishing. Comoros, Fiji, Grenada, Haiti, Kiribati, and Vanuatu are some of the most vulnerable, due to their limited capacity to adapt.

Aside from climate change, small island nations and their wildlife, often endemic, also face the threat of poaching, deforestation, and pollution. Habitat loss and competition from invasive species upsets animal populations and causes imbalances in the ecosystem.

Abundant marine life in the Pacific has attracted many foreign fishing outfits, who often practice harmful techniques that endanger the health and sustainability of marine and wildlife. Overfishing, destructive methods, and non-selective equipment all have costly, grave side effects.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, global demand for tuna and reef fish, like grouper and snapper, has created a spike in harvesting levels, from which fish populations do not have adequate time to recover.

Declining fish stock is hard to combat as the most catch from foreign vessels goes unrecorded, as they move in-and-out of these oceans. It is argued that non-selective gear causes the most inadvertent harm by trapping and injuring millions of non-targeted species, such as whales, dolphins, sharks and marine turtles, in the process.

The worsening effects of climate change are still the greatest threat to the Pacific SIDS. Warming waters are killing algae, the food of coral reefs, and further degradation is caused by high atmospheric CO2 level, of which the ocean absorbs one-fourth each year. This absorption increases the water’s pH, a phenomenon known as ocean acidification, making it more challenging for reefs to calcify and form hard skeletons.

Papua New Guinea is particularly affected by these stressors, with the area of reef threatened expected to rise from 55% to 100%.

The largest single threat to biodiversity in the AIMS is human exploitation of natural resources, which ranges from unsustainable agricultural practices and deforestation to illegal poaching.

Mauritius, home to the famous Dodoa symbol of species extinction—has continued to face exploitation of natural resources. The IUCN ranks the country as having the third most endangered flora in the world.

All endemic species in the Mascarenes are threatened, mainly due to loss of habitat from agricultural conversion and invasion from alien species. Hunting of endemic bats and marine turtles also occurs.

In Seychelles, 54% of amphibians are threatened with extinction, ranking the country ninth in the world from threatened and extinct amphibians.

Projects have been launched throughout the three SIDS regions:

The Caribbean Challenge Initiative (CCI) A coalition of governments and private sector partners working to enhance the conservation of their marine and coastal resources by 20% by 2020.

• The Micronesia Challenge Aims, by 2020, to conserve a minimum of 30% of near-shore marine resources and 20% of the terrestrial resources through-out Micronesia.

• The Coral Triangle Support Partnership (CTSP) Brings together science and local expertise to provide practical conservation and resource management solutions to the nations within the Coral Triangle.

• Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are another important effort to preserve biodiversity across the most vulnerable small island nations. Given that SIDS are primarily dependent, across multiple strata, on the wellbeing of their natural environments, many of them have taken measures to mitigate the negative impact of climate change. For example, in Kiribati, commercial fishing has been prohibited inside of the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA), which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, to stabilize their tuna population.